A few thoughts on why I think climate finance flows will remain resilient, across the capital structure, over the short and longer-term.

That trend will be non-linear but head up and to the right because climate finance provides tangible benefits that not only create positive environmental outcomes but that also promote sovereignty, productivity, resilience, and innovation – ironically, akin to what coal and the steam engine did in the 18th century onwards.

Originally posted July 8, 2024

A friend recently mentioned how they thought climate finance was a priority only in good times. My automatic response was to defend, but I knew similar questions had crossed my mind in the past. So, I thought the query was deserving of a more holistic response. The below is an excerpt of my inner thoughts.

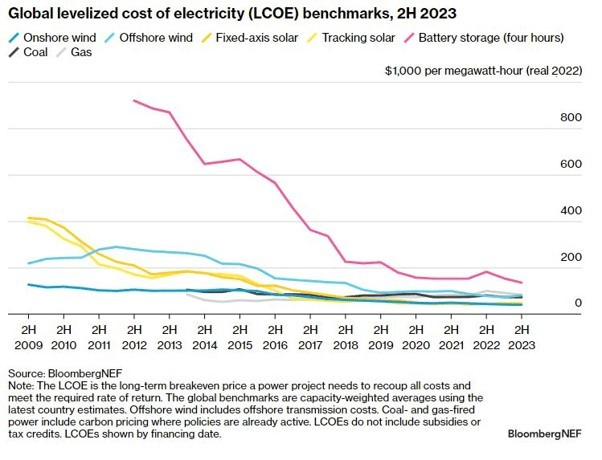

I will define the “good times” as the time when liquidity was bountiful, funding costs were low, and investors were seeking yield. COVID was not a particularly great time, but it was a catalyst for sustainable finance, for clean energy investment, and for social equity. From there, we saw a renewed focus on resilience leading to supportive policy. Take energy, the backbone of society. Since the 18th century, fossil fuels, namely coal, allowed for exponential growth in productivity, innovation, and living standards. But those “dark satanic mills” came with strings. Clean energy was the perfect way to facilitate a similar revolution whilst enhancing independence and resilience. It was also a sound economic decision because by 2020, the levelised cost of renewable energy for many countries was fast becoming cost-competitive with (and often better than) its fossil fuel counterparts.

Many (definitely not all) things in life are neither “good” or “bad”, rather a matter of perspective, this is no different. A uniform label across climate finance is far too blunt of an instrument. What applies in one asset class or one geography is not reflective of an entire landscape. What we can expect in climate finance, just like the broader capital market, are peaks and troughs correlated to shifts in the business cycle. Ultimately, it all hinges on economics and incentives.

Finally, before I get into the weeds, the question might seem counterintuitive considering the underlying tenet of climate finance is to solve a global, existential threat (i.e. something very difficult). But it’s critical to recognise that climate change is a longer-term, structural challenge, funded by a shorter-term, cyclical mechanism in climate finance. That means finding equilibrium between short-term and longer-term needs is like catching rainwater with your mouth – a little inefficient, and a little messy. All of that is to say, the trajectory will be nonlinear, but you can be sure that over the next decade, across the capital structure, we will see a trend upwards and to the right.

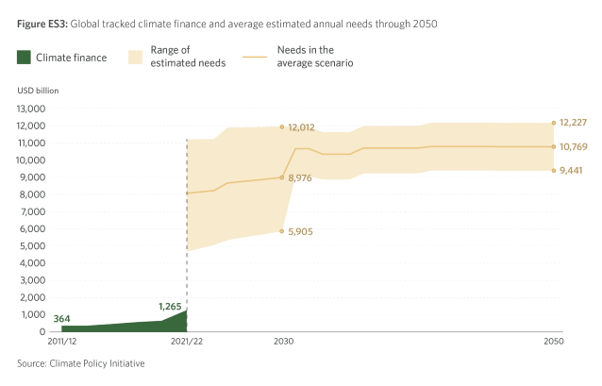

Climate Investment

To achieve net-zero by 2050, climate finance needs to scale ≥6x by 2030. That means investment (public + private) must grow from US$1.3t to US$8.5t per annum. By 2050, we will need US$10t. That figure is actually quite achievable if you were to aggregate and reallocate the trajectory of clean energy investment, along with fossil fuel expenditure. Clean energy investments will reach ~US$2t this year – double what it was a decade ago. Consider from 2014 to 2019 investment increased by a modest ~10% – the remainder of that growth – ~$900b – has happened in only 5 years. Fossil fuel investment in 2023 reached US$1.1t, add on the US$7t of subsidies, and presto we are now cumulatively at US$10t. In reality, fossil fuel investment and subsidies won’t go to zero, but a progressive reallocation of those incentives will have profound, broad-based impacts.

Priorities, incentives, and some economics

In isolation the climate finance piece seems tenable. But let’s play a little game of decision-making. Imagine you were Earth’s (benevolent) ruler. Your office sits 50km above Earth giving you an unobstructed vantage point. In front of you stands an anxiety-inducing 500-switch switchboard (think Homer Simpsons’ nuclear power panel). Each switch represents the needs and demands of various people, organisations and countries. In the middle lies an oversized green button, it pulses, getting brighter by the day – climate change. To its right though is interest rate volatility, to the left is geopolitics, underneath sits a slew of fiscal-related challenges, darting across the board is inflation, and in the corner is a curiously spongy button, oh its demographics. The point of this absurd visual is to convey the multitude of problems we face, and the difficulty in deciding what takes precedence.

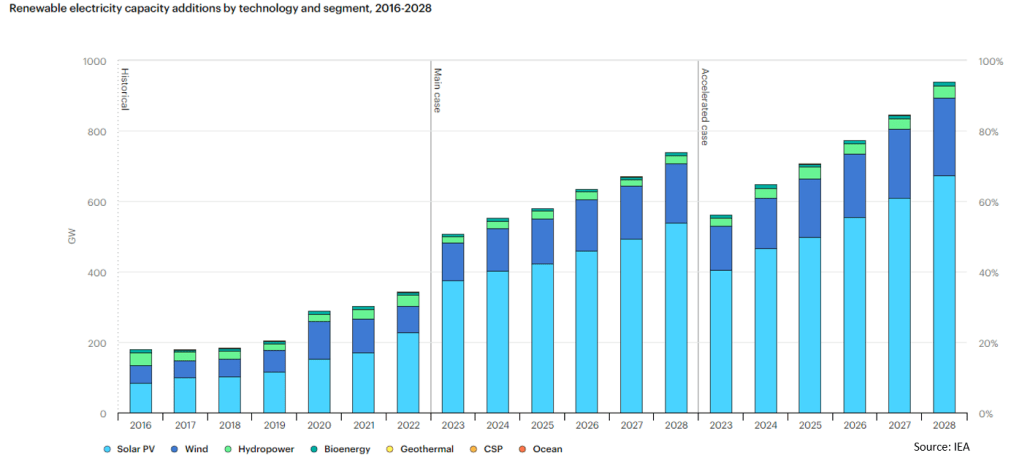

Despite those immense challenges, we have made considerable progress in areas such as energy systems and electrified transportation. There is plenty of debate about how we bridge the investment gap. My hypothesis is that we will see a power law-esque trend where ongoing electrification will enable a host of other solutions.

What’s changed?

For some time, I wanted to believe that the acceleration of climate finance stemmed from society’s recognition of the negative impacts from climate change, as it was for me. But there is no surer way to feel eternally disappointed than by assuming your perspective is aligned with the broader population.

The reality is that it is simply pragmatic to commit and invest aggressively in this space, for the sake of economic resilience, sovereignty, competition, innovation, and productivity. For very similar reasons of industrial revolutions centuries past it would be irrational not to adopt more efficient, effective, and cheaper solutions. Now, if history is any indication, irrational decision-making does not preclude less efficient decisions from being made but what is important is the general trend, not so much the hourly chart. Change will create pain, and pain will create a response. I consider this a normal part of a changing operational model.

Over the last ~5 years I think there has been a fundamental change in the perception of climate solutions. Irrespective of an investors motives – more productivity, emissions reduction/climate, social equity – the solutions to achieve each often intersect.

So many elephants, such little incentive

One of the elephants in the room though is the disparity between developed market (“DM”) and emerging market (“EM”) flows. Most of this isn’t surprising, I’ve talked before about the threshold for EM investment being more difficult, and about the burden of climate being far higher for economies with less adaptive capabilities.

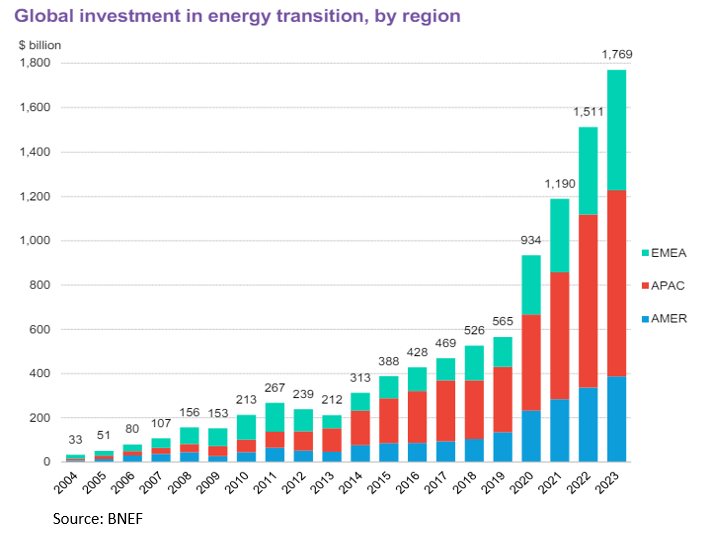

This encouraging chart from BNEF shows the exponential increase in energy transition investment, but it also highlights the most persistent challenge we face, regional capital concentration. EMEA includes Africa but European investment was 66% of regional flows, the USA accounted for 78% of flow in the Americas, and China accounted for 80% of APAC flows.

Consider the loss and damage fund. Talked about for years, formally introduced in 2022, and seeded in 2023, the fund attracted ~US$700m in pledges, 0.2% of what vulnerable nations will require. Why did it take so long? A lack of incentive. The EU pledged US$27m, the USA US$17.5m, and Australia didn’t participate. Could they have given more, of course. But more immediate challenges and priorities took precedence. To be fair, the EU, USA, and Australia have all meaningfully contributed towards the energy transition and developing regions, in numerous other ways – but thus far, have lacked the incentive to inject large amounts for this particular vehicle.

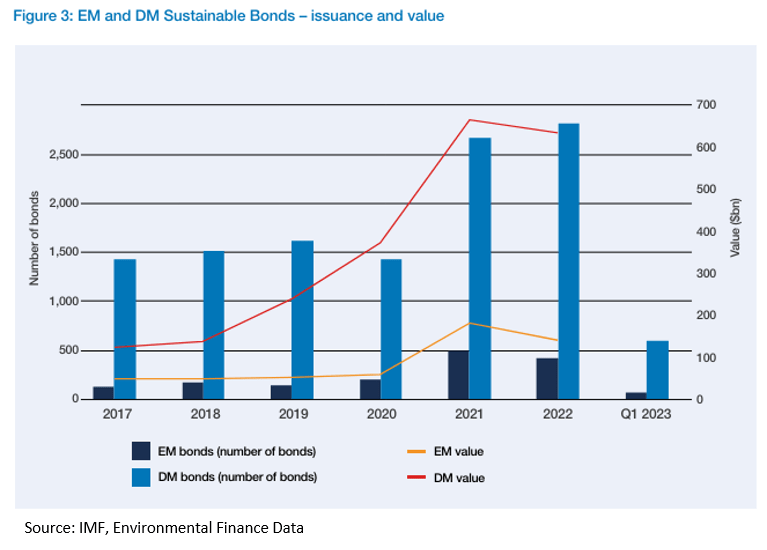

There are however bright spots. Improvements in regulatory frameworks, data availability, and supportive policy, are all contributing towards increased private investment. In Asia (ex-China), that is bringing liquidity into areas such as infrastructure, energy, and transportation. The EM sustainable bond market has also seen a ~4-5x increase from 2017 in terms of volume and value. Innovative structures – including wildlife bonds, blue bonds, and debt-for-nature swaps – have also helped to deepen and diversify the investor base.

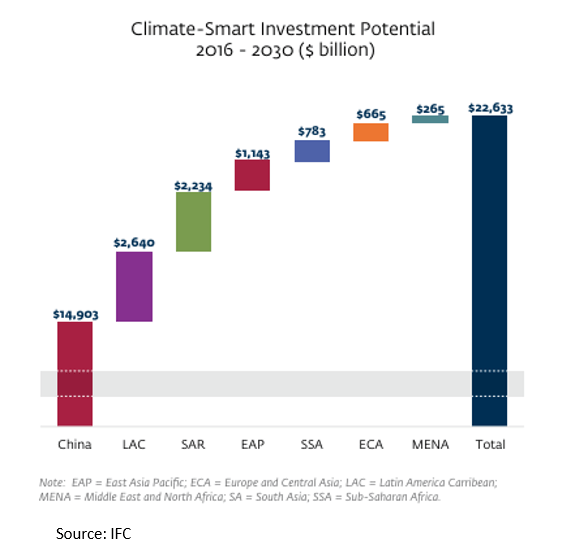

Ultimately, solving EM clean energy investment hinges on privatisation and cooperation. If we assume that is true then better governance, transparency, and supportive policy will help to reduce cost, simplify processes, and mitigate risk. In aggregate, we should then see an influx of domestic and foreign capital inflows. Historical reliance on domestic public funding has led to inefficiencies, whilst conservative appetite in private capital has constrained capital investment. Multilateral financing is important but overreliance will lead to high leverage – I saw both sides of this in Nepal. The challenge is unlocking the investment potential (US$23 trillion according to the IFC) by introducing the right incentives to stimulate change and to attract investors.

As humans, we are terrible at understanding non-linear outcomes, but whilst that lack of comprehension undoubtedly contributes to inaction, it does tend to stir some sense of urgency once it (eventually) comes to the fore. That is happening right now, and we are seeing climate finance permeate rapidly through capital markets, even if it means taking a quick breather.

Leave a comment