Originally posted August 9, 2022

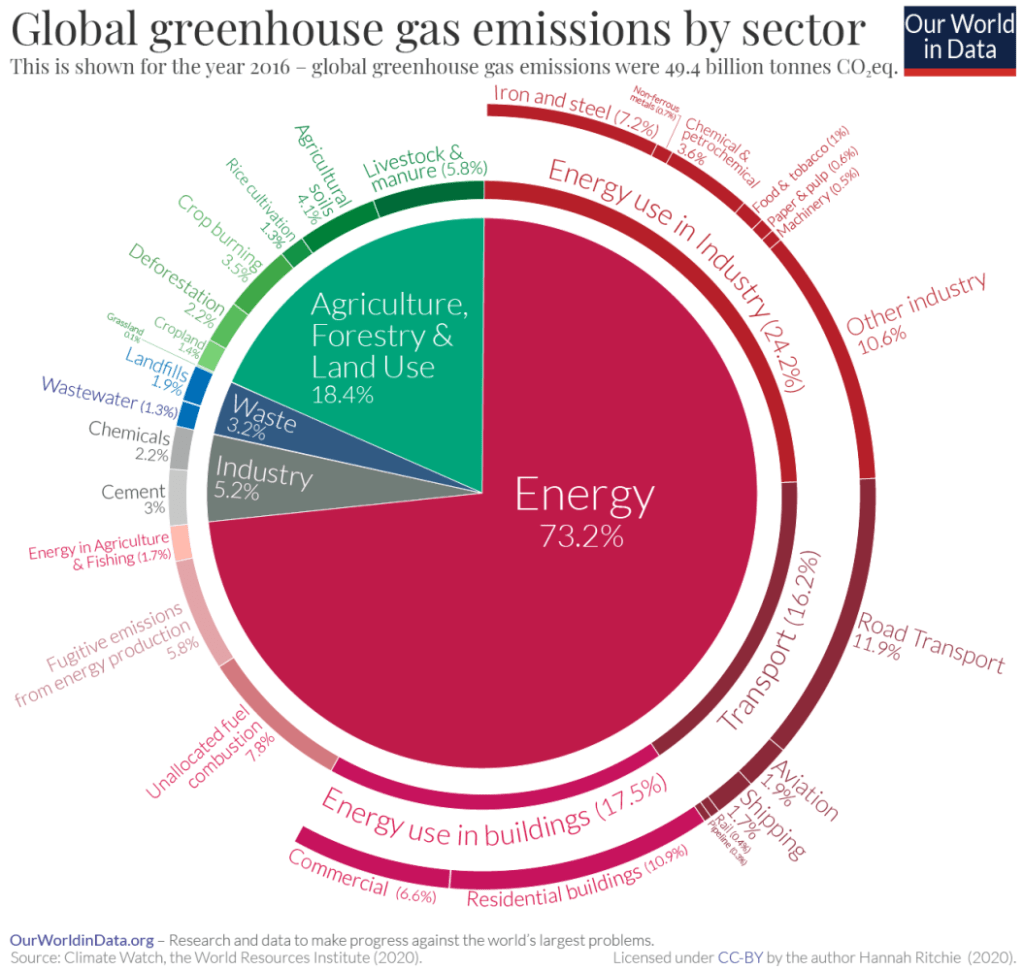

Transportation accounts for ~16% of global energy-related CO2 emissions. Within that wedge lies the shipping industry, a sector that accounts for ~2% of global emissions and transports ~90% of world trade – acting as a critical link for trade partners. This linkage also means that as these same trade partners look to improve their broader emissions footprint and procurement practices, added focus is placed on vessel operators and their own sustainability efforts.

Considered one of the “hard-to-abate” sectors (because prospective low carbon solutions carry a higher abatement cost than existing, higher carbon, technologies), the industry continues to explore various avenues to align to with a low carbon economy. With that in mind, what are the challenges and opportunities within the industry, and how quickly can we execute?

First, some context.

- In 2020, the total volume of goods shipped globally amounted to 10,648 million tons, representing a more than 400% increase over the last 50 years.

- The sector is, by far, the most economical and efficient means of transporting goods. Direct CO2 emissions per distance sees deep-sea vessels (namely bulk carriers, tankers, containers) within a range of ~3-20 gCO2/km. In comparison long-haul cargo aircraft stand at ~500 gCO2/km. A lot of this is to do with the sheer size of merchant vessels – the largest container vessels are north of 23,000TEU (equivalent to 552,000 Mt) whilst the largest cargo planes hold a maximum payload of 130 Mt (yes, container vessels really are huge).

- The International Maritime Organisation (“IMO”), a United Nations agency that serves as a core governing body for the sector, introduced the IMO GHG Strategy (“Initial Strategy”) in 2018, committing to:

- A carbon intensity reduction of 40% by 2030 (2008 baseline)

- A carbon intensity reduction of 70% by 2050 (2008 baseline)

- A GHG absolute emissions reduction of at least 50% by 2050 (2008 baseline).

- In 2020, the IMO capped the global sulphur limit of bunker fuel to 0.50%, down from 3.50%. The mandate was a positive step in reducing air pollution from ship exhausts.

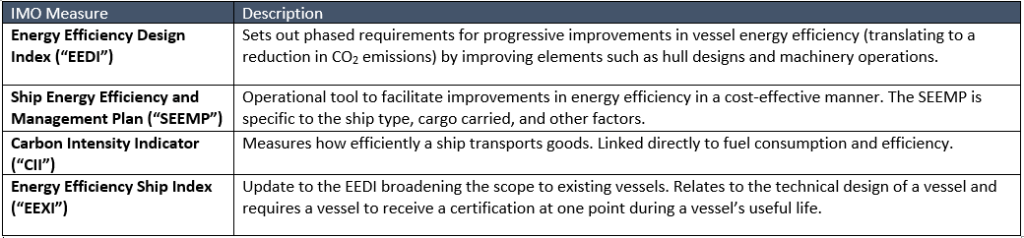

- Since 2007, a combination of technical and operational improvements are estimated to have reduced energy use and CO2 emissions by up to 43%, that may increase to 60% by 2050. Underpinning these improvements are a few key measures introduced by the IMO, first in 2005 and to be further strengthened from 1 January 2023.

- The Initial Strategy is likely to be refreshed and strengthened in 2023 as stakeholders continue to push for greater ambition and alignment with the Paris Agreement.

The industry has three primary levers by which to decarbonise.

- Fuel choice (adoption of transition and zero-carbon fuels)

- Design improvements (hull designs, coatings, propulsion systems)

- Operational efficiency gains (increasing economies of scale, route optimisation, slow steaming)

These levers present challenges and opportunities for the sector. We know from above that there have been major design and operational improvements, generating double digit efficiency gains over time. What we haven’t explored yet is the other important (and of course challenging) component, fuel choice.

Alternative Fuels

In the absence of commercially viable zero-carbon fuel sources, many stakeholders have turned towards liquified natural gas (“LNG”) as a transition fuel. A switch to LNG improves the energy efficiency and CII by ~20%, whilst emitting significantly less air pollutants (almost no sulphur oxide and ~80% less nitrogen oxide). However, whilst LNG contains less carbon per unit of energy than bunker fuel, on a lifecycle basis, GHG emissions reductions may be negligible depending on the level of methane slip (i.e. unburned fuel that is not fully combusted in a ships engine, escaping into the atmosphere).

Most stakeholders recognise LNG is not a panacea with many now evaluating cleaner fuel sources, namely hydrogen, ammonia, methanol, and biofuel. The challenge at this point in time is how to scale these fuel sources to improve technical and economic feasibility. So let’s first have a look at some key considerations for hydrogen, and move to some alternative fuels likely to supplant fossil fuels for long-haul deep-sea shipping (electrification may play a larger role in short-haul shipping).

Hydrogen

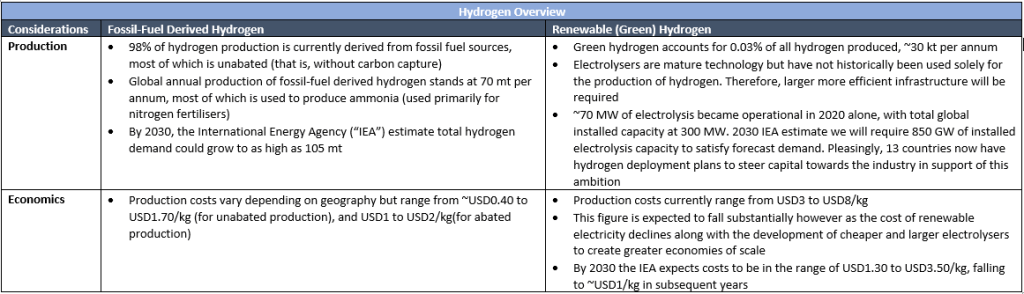

Hydrogen production faces a number of barriers before production, through renewable sources (i.e. green hydrogen), is proven at scale. Production is currently dominated by fossil fuel sources, and the cost of green hydrogen is naturally more expensive owing to a market still in its infancy. However, as renewable generation continues to expand, the input costs for electrolysis (see below) will continue to decline. Supplement that trend with ongoing efforts to increase electrolysis capacity and we are likely to achieve commercially viable green hydrogen in the not-so-distant future.

Alternative Fuels

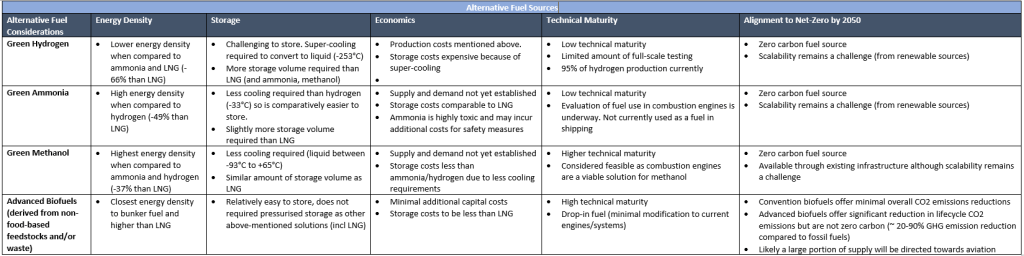

Energy density (in liquid form because this yields a higher energy density), storage (both in terms of space and cooling required to convert into a liquid form), economics (demand, supply, and the resulting cost), technical feasibility (technological maturity, implementation with current engines/systems), and of course alignment to a net-zero by 2050 economy, are all key considerations for the suitability of an alternative fuel.

Looking Ahead

What you’ll probably discern from the above table is that each fuel source has the potential to be a critical decarbonisation enabler. However, irrespective of fuel source, each faces a scalability issue that traces back to technical immaturity, translating to a lack of supply and a need for direct investment. Of course, for that to occur there also needs to be an investment thesis supported by clear demand factors.

To do so requires a concerted effort from stakeholders across the value chain from policy-makers to vessel operators. Already companies and countries have mobilised to establish a cleaner fuels ecosystem to support demand for a range of uses over the coming years. The EU has taken steps under its Fit for 55 package to not only strengthen emission reduction targets but to also boost alternative fuel infrastructure at ports, and the US Climate Bill will see support for cleaner fuels (namely biofuels and green hydrogen). The IMO of course plays a vital role in all of this to create a cohesive, far-reaching governance framework. That strengthened, and much needed, framework is expected in 2023 and will hopefully align with Paris whilst providing much needed clarity to operators.

There are very real challenges ahead for the sector, but such a transformation also presents exciting opportunities, we just need to press ahead.

Leave a comment