Three of Japan’s largest automotive manufacturers, Honda, Nissan, and Mitsubishi, are thinking of merging. Once titans of their industry, these manufacturers risk falling into obscurity if they can not innovate and pivot. Ironically, it was the same cohort decades prior, that dominated much of road transport by introducing lower cost, high quality vehicles – the same challenge they now face. Whether the merger goes ahead is less relevant than what the plan represents – generational secular upheaval.

If we look back over the last two decades, we can see what brought us here, what we can expect in the next decade, and why we are beyond the inflection point.

Two decades of automotive progress

Have you ever compared a car from the 1980s to one built in 2005? If not, have a quick look at how the Honda Accord has evolved over that period. From the no-frills, boxy 1980s model to the sleek and curvaceous 2005 edition. But whilst my 2005 Honda Accord provided me GPS, heated seats, and Bluetooth – the underlying engine technology was fundamentally the same, an (better designed) internal combustion engine.

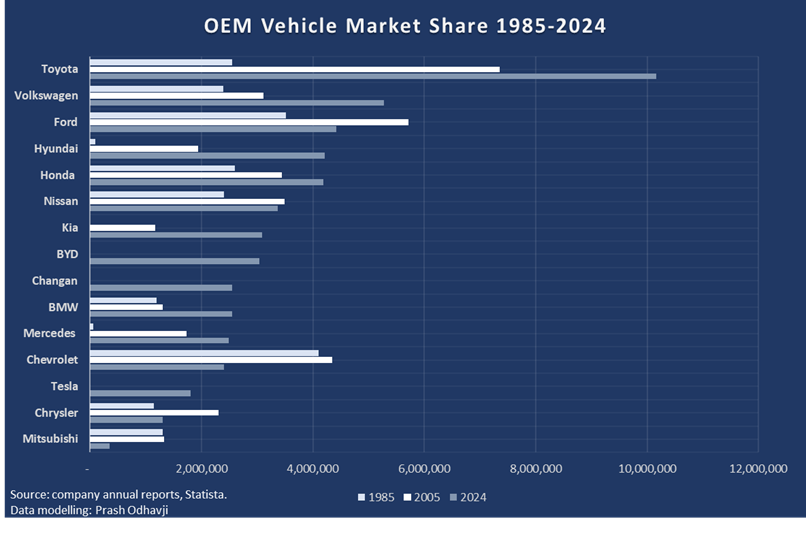

Within this period the passenger vehicle landscape has shifted dramatically. The last 5 years, have been particularly transformational. In 2005, Japanese (16%), US (28%), and European (17%) manufacturers accounted for ~60% of global car production. China had an 8% share. By 2024, China’s market dominance was unequivocal, 35% of global production. The other four regions declined to a cumulative share of 44%.

At this stage it is important to recognise that China’s eventual prowess in EV production was not simply a product of an exponential increase in industrial capacity. It was underpinned by a highly integrated and systematic approach across the value chain.

Awakening the sleeping dragon

Napoleon once referred to China as a “sleeping dragon”. In two decades, China saw that foresight come to fruition.

In the early 2000s, China became fixated on establishing and fostering a domestic vehicle manufacturing industry. This emphasis, as with most of China’s other policies (energy, agri, tech/AI) is based on reducing reliance on foreign influence to create a self-sufficient economy.

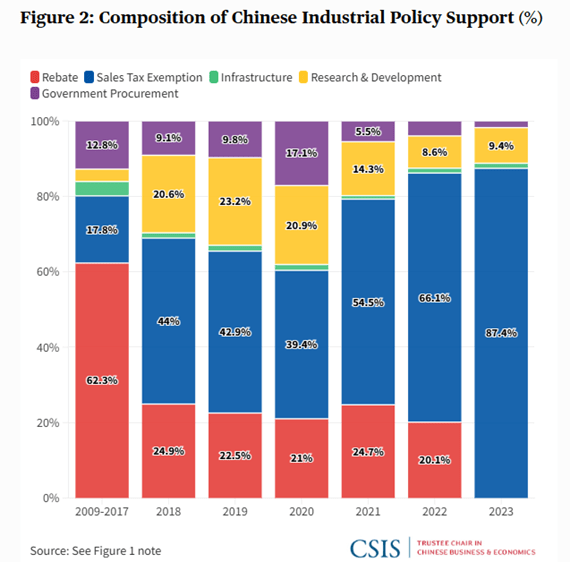

In the late 2000s, heavy government support for R&D was crucial. Manufacturers like BYD, Geely, and Changan began to thrive. But, subsidies are not unique to China, nor do they explain the success of the Chinese approach. European subsidies total US$46b per annum and the USA provided (in the form of a loan) US$51b to General Motors alone to support its restructuring efforts. China meanwhile is estimated to have provided US$231b over 15 years (roughly US$15 per annum). The differentiating factor was the nature of the approach, one looked forward, the other set its eyes on maintaining the status quo.

By the 2010s China’s influence began to trickle outwards. The “Made in China 2025” initiative, inspired by Germany’s “Industry 4.0” plan, made clear its intent for Chinese industry to become an influential, and self-sufficient entity within selected technolgoies ranging from AI and robotics to energy, biopharmaceuticals and agriculture.

Leadership through integration

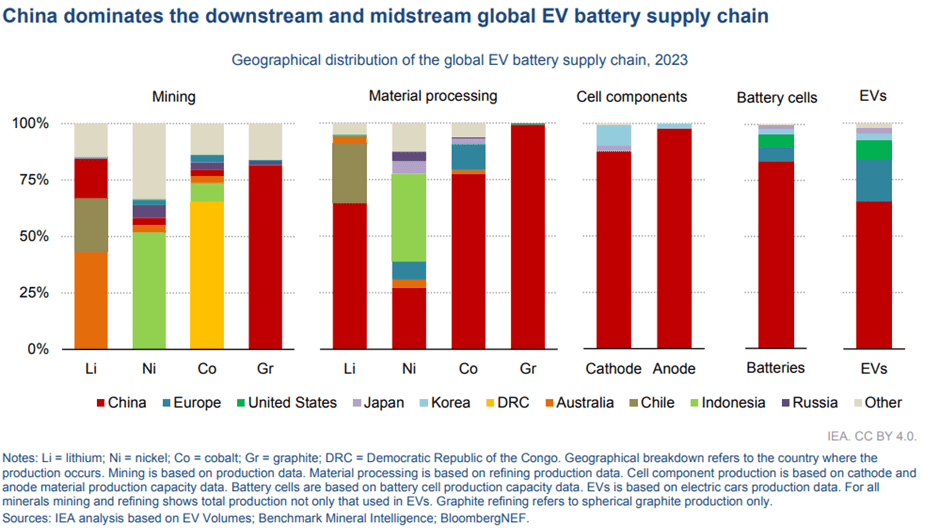

In 1987, Deng Xiaoping said, “the Middle East has Oil, China has rare earths’. But that was just the beginning.” Xiaoping’s comment touched on how China was building and was already the dominant player in the mining industry. Its pre-emptive approach enabled China to rapidly integrate its mining dominance into value-add products including lithium batteries and ultimately, EVs.

Today, China control upwards of 75% of the EV supply chain (see diagram below).

Stagnation

Whilst the 1990s marked a period of growth for China, it marked a challenging period for Japanese companies. After the steep decline in the value of real estate and equities, growth remained slow and unemployment high. Structural challenges persisted through the 2000s in the form of an aging population, declining birth rates, and fiscal imbalances.

The performance of Japanese automotive manufacturers in the 2000s varied. Toyota and Honda experienced broad-based success through well received car models. After a restructure, Nissan was also able to return to profitability. All three introduced alternative technologies, hybrid (Toyota and Honda) and for Nissan, one of the first mass-market EVs (Nissan Leaf). Despite their early innovation, Japanese manufacturers saw these alternative technologies as fringe products rather than a replacement to the internal combustion engine (“ICE”) vehicle. At the time, range anxiety, low battery densities, and minimal charging infrastructure meant that investment CAPEX would be in the trillions. Such a pervasive shift is not something many manufacturers, not just the Japanese, saw happening in the next decade. It was however particularly pronounced for Japanese manufacturers given their respective ICE vehicles remained highly profitable.

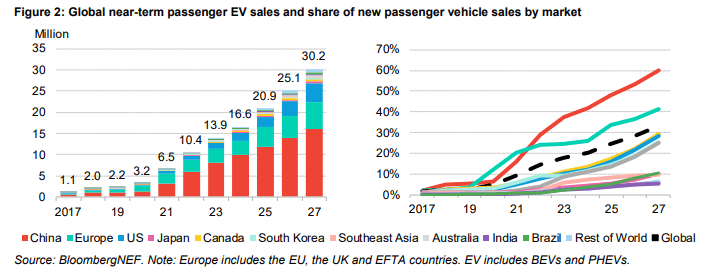

Of course, EVs turned out to be more than a niche market over the coming years particularly in markets outside of Japan, primarily Europe and the USA.

To merge or not to merge

Mergers and acquisitions typically occur in two broad forms, either the acquirer seeks to target a company within its industry, or, to enter a new market using the acquisition as the initial platform. Both seek to generate “value”, namely a stronger, more profitable business.

The most obvious question then is what value would be generated between a merger of Honda, Nissan, and Mitsubishi? Each company boasts a well-established ICE product range, would result in immense global reach and economies of scale, allowing for more efficient use of capital for future R&D. But it all comes back to integration. Each of these potential benefits is only possible if integration can happen in an efficient, cost-effective manner underpinned by sound reasoning and decision-making. In short, how do you trim the excess fat without losing (but rather gaining) lean muscle.

So far, we’ve looked inward. If we take a more existential, outward perspective, how much of this will matter in 5, 10 or 20 years? Integrating a company, or three large companies, can take several years. If the goal is to remain competitive on a global scale for the foreseeable future, is years of post-merger integration planning conducive to forming an innovative and financially viable company that needs to be adaptive?

Consider these insightful nuggets:

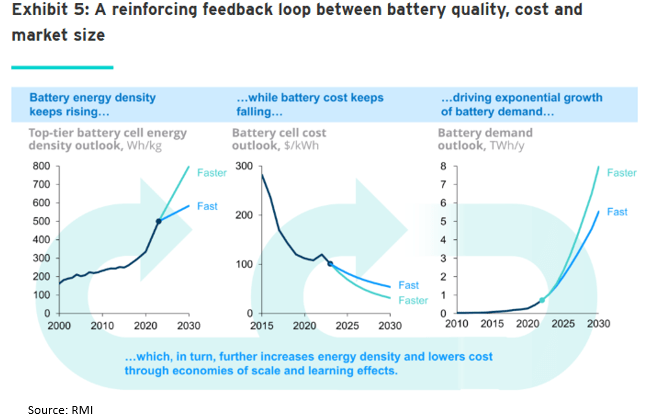

- Within 5 years, sale of EVs went from 2% to 18% globally

- Within 5 years, battery recycling capacity is forecast to increase 50%

- Within 5 years, battery demand is expected to increase 600%

- Over 30 years, battery costs have fallen by 99%

In that context, 2 years is a long time to be away from the wheel (even more so if self-driving technologies gain widespread adoption).

Leave a comment