A few months ago I posted about the cost of capital (“CoC”) disparity between developed and emerging markets, and why it remains a vital component of accelerating decarbonisation.

But what would happen if the CoC in emerging markets reached parity with developed markets?

The barriers to emerging market financing is well known. But a recent study went a step further to integrate real-world financing costs into climate-energy-economic models to quanitfy how financial disparities impact clean energy investment. It explores a CoC convergence method where financing costs in developing nations are reduced to match those in developed countries by 2050.

The overall finding, convergence in CoC reduces emissions, accelerates deployment, and enhanced electricity accessibility.

TLDR

✔ The study used empirical CoC estimates, widely adopted integrated assessment models, and scenario designs to reduce biases in model-based projections.

✔ Renewable energy projects are more affected by higher financing costs than their fossil fuel counterparts due to their capital intensity. Some technologies face a higher risk premium due to their relative immaturity – this will improve over time with more deployment/track record.

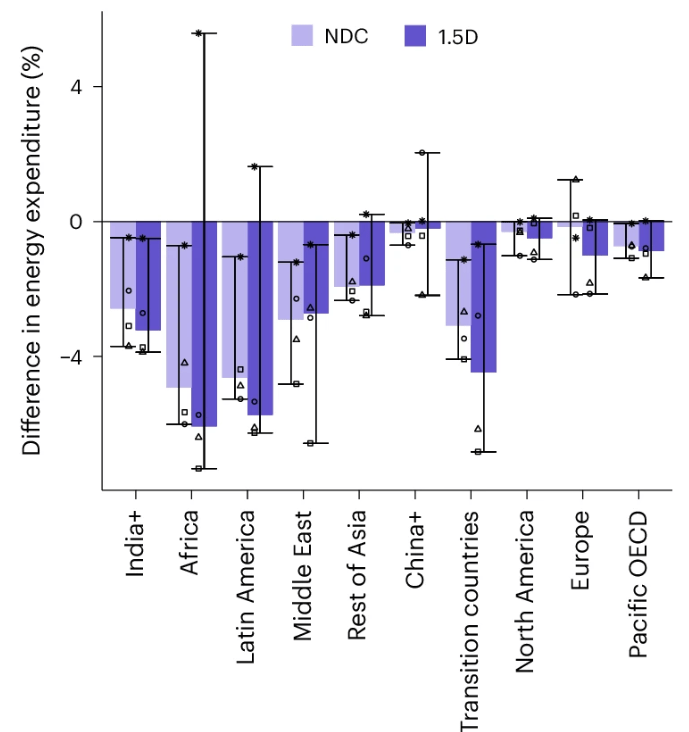

✔ Convergence lowers energy spending as a proportion of GDP in developing countries, India ~2%, Asia (ex-China) ~1.5%, Pacific OECD ~0.5%.

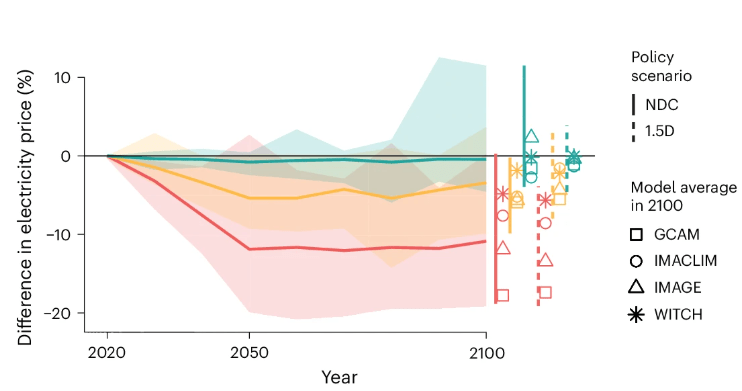

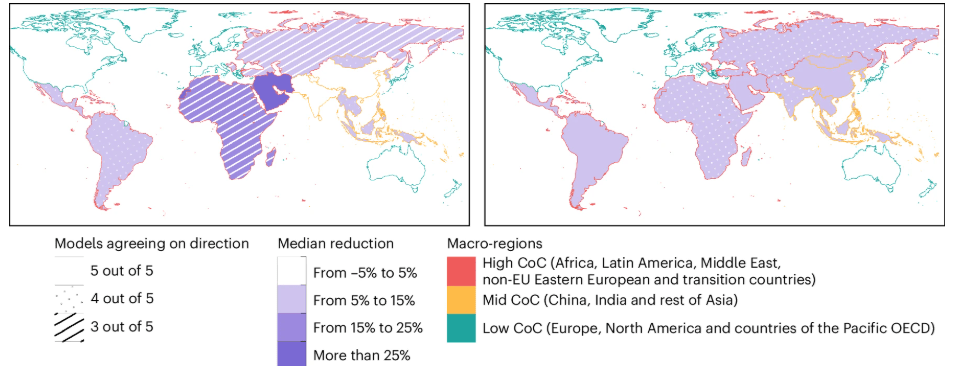

✔ For Asia (incl. China) convergence would see, ~10% increased demand for renewable electricity. ~10% lower electricity prices in Asia (China, India, rest of Asia) by 2050. 5-15% carbon intensity reduction of electricity.

✔ Bringing about such convergence would mean, lower country risk profiles, better energy system sypport policies, greater depth and breadth of multilateral guarantee mechanisms.

5 more minutes? Read on…

What inputs and assumptions are included within this study? Are these realistic?

- Modelling was bused on the use of empirical CoC estimations using country and technology specific financings costs.

- The CoC data was then integrated into widely used integrated assessment models (“IAMs”). IAMs fused societal, economic and environmental considerations. It therefore looks to improve these IAMs by providing more granular and specific data that would in turn better support decision making for policy-setting and financing.

- CoC for fossil-fuel based power generation was based on balance sheet financing for major utilities in each country. Renewable (ex-Hydro) CoC was based on country-level debt and equity project finance. CoC was then split into different components, namely country and technology risk.

- The model was then evaluated under two climate policies. The first, a nationally determined contribution scenario where commitments were reached by 2030 (equivalent to a 2.6 degree scenario), and second, an idealised net-zero scenario that would cap warming to 1.5 degrees.

- The study is comprehensive. A key assumption however, was that over the next 25 years energy financing would be equal in all geographies. That reality is unlikely but the study remains an important though experiment.

What are the key benefits of CoC convergence?

- Average spending in developing countries as a % of GDP declines materially. As much as ~6% in Africa, ~2.5% in India, and ~1.5% in Asia (ex-China).

- More renewable electricity is generated and concurrently, the price of electricity falls.

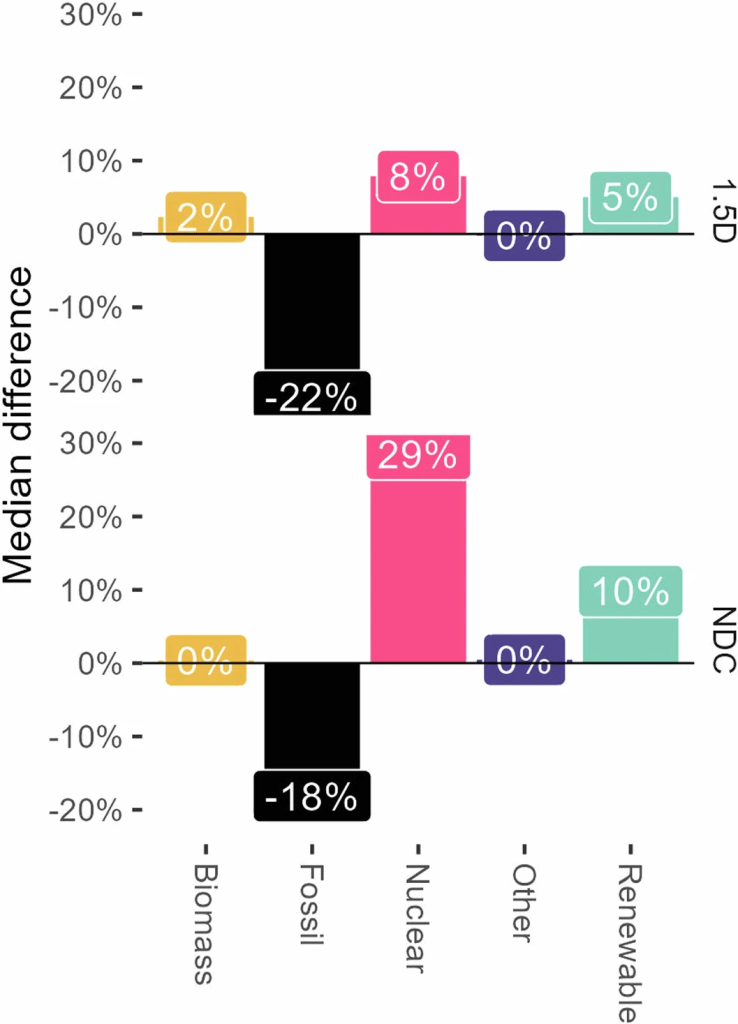

- Energy mix shifts markedly towards cleaner energy sources.

- A robust reduction in carbon intensity occurs. Interestingly under the net-zero scenario the primary benefit of CoC convergence is not lower emissions but the lower cost of achieving stringent climate policies to reach net zero.

- Importantly, CoC convergence sees a reduction in inequality by enhancing accessibility to energy. Inequality per capita of renewable energy generation is ~3% lower, whilst renewable capacity equity improves by ~2 points in the Gini index.

How could we progress towards CoC convergence?

- Lower country risk profiles/premiums – this is largely dependent upon structural issues such as macroeconomic/political stability, governance considerations, capital markets liquidity.

- Develop (renewable) energy sector-specific policies – supportive policy can help lower the cost of renewable energy deployment, electricity market designs to improve pricing, support for grid system flexiblity, accelerate permitting and planning.

- Implement policies to improve financing conditions – deeper and broader de-risking instruments from development banks, auctions underpinned by multilateral guarantee mechanisms, and expanded private financing inflows will go a long way to accelerate deployment.

Bottom line

High financing costs are nothing new. The market has discussed a just transition for a number of years now but nominal financing costs have always been a key barrier. With rate cuts priced in for 2025 and beyond, the coming period may allow for an idyllic period of lower funding costs and greater (clean) energy accessibility, all of which points to economic growth (via increased productivity).

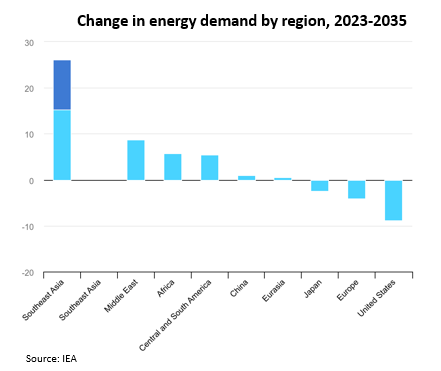

South East Asia will see outsized energy demand over the coming decade, what the energy mix looks like will rely quite heavily on the ability to finance the most productive and economical assets.

Source (material + graphs): https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-024-01606-7#Sec4

Leave a comment